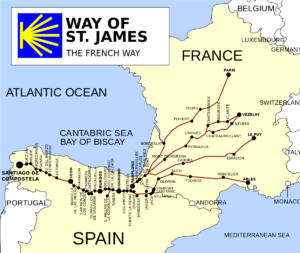

In medieval times, walking a pilgrimage to Santiago began the moment your foot left your doorstep to make your way to the Cathedral of Santiago de Compostela– usually on foot, possibly with a burro or horse, perhaps as a mendicant, perhaps as a king or queen. But to make a pilgrimage was an intentional commitment to put aside a period of your life to submit completely to the Way of Saint James, also known as the Jacobean Way. The journey could take more than a year to complete!

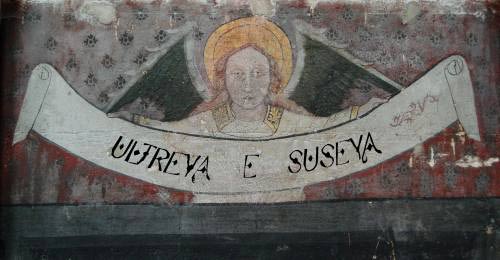

The early pilgrim had no options to return by train, bus or airplane, but had to return the same way that they came–on foot, or horse or burro. It is said that pilgrims on their way to Santiago would exhort other pilgrims with the salute: “Ultriea!” which translates roughly as “Onward!”and pilgrims on the return journey back to home would shout the greeting, “et Suseia!”– roughly, “and Upwards!”

(These words appear in the 11th century hymn, Dum Pater Familias, which appeared in the Codex Calixtinus. The Codex is a medieval anthology of detail and advice for pilgrims following the Way of St. James to the shrine of St. James the Great, in the Cathedral at Santiago de Compostela. Today’s Codex is more likely to be the Brierly handbook with its detailed maps and descriptions about the physical and mystical path, but the idea is the same.)

As for me, the modern pilgrim, I know that I can take an airplane after my two week walk and be home by a specific date to return to my normal routine. But one is never the same after a pilgrimage, whether it be for two weeks, two months, or two years. The Camino has its way with you in the most subtle of ways. Gently unfolding, the road you traveled physically now moves internally, like a wispy travel weary map with deeply furrowed and beaten pathways, reframing your inner landscape over time, much more time than the time spent on the walk itself. If you have even walked a labyrinth, you understand this effect of the walking journey, no matter its length.